Alexa Travels > The Journey > Humanitarian Musings > Stepping into the World’s Largest Refugee Camp

Stepping into the World’s Largest Refugee Camp

Muhommad, a young father with a coarse beard and deeply etched lines in his forehead, invites us into his home. The shelter is small and stuffy; two rooms constructed of bamboo and enclosed by layers of heavy plastic sheeting, which serves as the only separation between their loved ones and the bustling mega-camp outside.

Muhommad’s elderly father smiles at us through red paan-stained teeth, proudly wearing a faded white tupi, indicating he is a man of faith. Muhommad’s five-year-old daughter and three-year-old son watch us, wide-eyed. His wife, Sumaiya, rapidly unfurls an expertly woven straw mat across the dirt floor for us to sit on—our eyes watering from the smoke of a small cooking fire burning in the next room. The interview lasts about thirty minutes, as questions about the household are asked by a local team member. Sumaiya’s eyes drop to the earthen floor as she mentally relives the seven days it took them to arrive in Bangladesh on foot, the family members that were killed before they fled, their village which was burned to the ground, and her three-month-old infant they lost along the way.

My first experience in the sprawling refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh was in October of 2017; just months after clashes between Rohingya (a primarily Muslim ethnic group in Myanmar) and police in Myanmar sparked a military campaign of violence. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya fled to the relative safety of Bangladesh. I was called in on assignment; my first mission in South Asia and the most raw displacement context I have ever ventured into.

The world’s largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh

The dry earth crumbled beneath my feet as I scrambled my way to a vantage point in the camp. Fanning out before me were the endless rooftops of shelters rising and falling with the curvature of the landscape. Etched into hills, carved into cliffs, crammed into ravines; land that was once dense forest sacrificed to create space for the families who fled Myanmar with nothing more than the clothes on their backs. It was difficult to comprehend where the world’s largest refugee camp began and where it ended.

That title of “world’s largest refugee camp”, a distinction no nation is vying for, was most recently attributed to Bidibidi, a vast settlement of 285,000 refugees in northern Uganda that sprang up as people fled civil war in South Sudan. For many years prior to that, the sprawling Dadaab complex on Kenya’s border with Somalia held this dubious honor, accommodating more than 200,000 refugees of the Somali civil war. At the time of writing this article, it is estimated that more than 900,000 Rohingya have sought shelter in the refugee camp of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

Rohingya mother and her two children

To understand the most rapid flood of human beings across an international border in recent history, some historical context is key. Britain colonized and administered Myanmar (previously Burma) from 1824 until Myanmar’s independence in 1948. As part of their divide-and-rule policy, the British were said to have favored the Muslim population at the expense of other groups. Tensions heightened later during World War II, when the Rohingya sided with the British, while Buddhist Myanmar nationalists sided with the Japanese. Following the war, for their loyalty, the Rohingya were awarded prestigious government posts by the British. This was never forgotten by the rest of what is now a sovereign nation.

For the Rohingya, the situation deteriorated drastically following a military coup in 1962, when Rohingya were ousted from political office and over time their rights eroded even further. Today the Rohingya are an incredibly marginalized group within Myanmar. Despite a Rohingya presence in modern-day Myanmar since the 12th century, they are not considered one of the 135 official ethnic groups, and have been denied citizenship since 1982—effectively rendering them stateless. The largest stateless population in the world, in fact.

The government and greater Myanmar populace refuse to even refer to them as Rohingya, instead referring to them as “Bengalis” (inferring that they belong to Bangladesh). Nearly all Rohingya in Myanmar lived in the Rakhine State, from which they are not allowed to leave and which they can hardly call home; given they are unable to hold property rights, have poor access to health care or education, and live in abject poverty.

Myanmar has a horrific history of state-sponsored violence periodically sending Rohingya over the border into what is now Bangladesh. In turn, the Rohingya in Bangladesh have periodically been pushed back into Myanmar. In 1977 and 1978 more than 200,000 Rohingya crossed the border, fleeing widespread human rights violations and evictions by the Myanmar military. Soon after, coercive repatriation programs and declining camp conditions in Bangladesh camps forced more than 180,000 Rohingya to return to Myanmar by 1979.

Increased Myanmar military violence again prompted an exodus of an estimated 250,000 Rohingya across the border into Bangladesh following elections in 1990. A resurgence of conflict and military activity resulted in an additional 87,000 Rohingya crossing into Bangladesh in October 2016. Violent backlash against the Rohingya in August of 2017 culminated in a level of violence which has been called a “textbook example” of ethnic cleansing and that the world was on the verge of declaring a genocide.

The Rakhine State of Myanmar (red) and Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh (yellow) Source: Wikipedia Commons, 2017

Refugee camps, as a rule, are a bizarre experiment in balancing incentives. On one hand, you have humanitarian organizations trying to provide for basic needs (water, food, shelter, healthcare, education) on the other hand you have host governments not wanting refugees to be so comfortable that they are tempted to stay. Further, the Government of Bangladesh has periodically threatened to relocate many Rohingya to uninhabited islands in the Bay of Bengal—a perilous proposition considering these islands are barely above sea level and climate change threatens to submerge them in the future. This setting is arguably more fitting for a prison than a refugee settlement.

With the ebb and flow of government policy and popular opinion over time, aid delivery in Cox’s Bazar has been reduced or temporarily halted out of concern that adequate living conditions would create pull-factors—encouraging other Rohingya to cross the border from Myanmar. Fearing any sense of permanence, Bangladesh has prohibited the creation of shelters of good quality. As such, the shelters in Cox’s Bazar range from older era sweatboxes of sheet metal walls and roofs—suffocating on a hot and humid South Asian day—to more recent and rapidly constructed shelters of bamboo and plastic sheeting, conspicuously emblazoned with bold UNHCR logos. The arrangement inside each shelter varies slightly, but many are dark and dingy, further darkened by the soot of indoor cooking; brightened only by the occasional swathe of bright fabric, wall art from magazine cut-outs, or the smiles of the occupants.

Rapidly constructed shelters utilizing every available space

Rapidly constructed shelters utilizing every available space

A swathe of orange fabric brightens up an older refugee shelter

The prohibition of building permanent structures in the camp has also impacted the sanitation system. Taps are opened for only two hours a day in many areas, severely restricting access to water. When I arrived at the peak of the human tide in October, we were hearing reports of women who had fled without their more modest hijab, niqab, or burqa (clothing which many Rohingya women would wear outside of the home). Feeling exposed in the jostling cacophony of the largest refugee camp in the world, there were accounts of women purposely lessening their water intake to reduce their trips to crowded and dirty latrines. A frightening thought in the hot, muggy Bangladeshi heat.

The extreme population density in the camp, where shelters fight for space on every available patch of land, along with poor water and sanitation facilities contribute to the outbreaks of Diphtheria and measles and high rates of diarrhea taking a harsh toll on the youngest and oldest.

Water jugs lined up in anticipation

I was struck by the resiliency of the Rohingya the first time I saw them in the camp. Proud Rohingya men walk through the camp with their signature lungees wrapped tightly around their hips. This single piece of looped cloth, often a plaid pattern, is wrapped and tied at the waist forming a ball, a signature of Rohingya men. When the men squat during a conversation among their peers or visitors, their young children sometimes squirm their way to the lungee hammock that is created between their legs. The women’s attire is much more varied, ranging from colorful dresses with flowy hijabs, to shorter sleeved bodices and a swath of fabric curled around a loose bun, to striking full ebony dresses with burqas.

Two Rohingya women (left) being interviewed

Despite the love which undoubtedly binds families living in these small shelters, the lack of privacy and space is a perpetual issue. Attempts among some to preserve the practice of purdah–keeping women away from unrelated me–is difficult in a hectic, crowded camp. Due to this, some women leave their shelters very infrequently. The high number of respiratory infections is likely related to overcrowding and the practice of cooking inside cramped shelters.

Navigating my way through the camp, I witnessed steep inclines, shelters perched precariously on recently cleared earth, etched into the side of a hill that threatened to give way. The recently excavated earth alternates between two settings: dusty, parched earth or slippery, sucking mud. These conditions leave Rohingya families very exposed to floods, cyclones, and landslides; something Bangladesh is infamous for.

A bamboo bridge over a canal in the camp

Refugee camps are also not designed for the occupants—they are designed for the administrators. When possible, shelters are arranged in rows, numbered and named by block to improve identification. In one of the newer Rohingya camp areas, large billboard-style signs screamed out “Block A”, “Block B”, “Block C” etc. With the number of people crammed in one place and the endless lines for food and drinks, the din of the scene below harkened images of an extensive outdoor event. Refugee camps are like an enormous music festival—except there is no music and you don’t get to leave, I thought sarcastically.

Cultural considerations, such as ensuring latrines do not face towards Mecca, are important but often overlooked. Large signs gleefully advertising “Baby Play Area” or “Blanket Distribution” are printed in English only, not the rarely written Rohingya language of the refugees, or even in Bangla, the national language of Bangladesh. Suspiciously Caucasian-looking faces are posted onto the latrines to designate them as “male” or “female”. It quickly becomes apparent that the welcoming signs are not for ease of navigation by the Rohingya, but for an international audience.

A very non-Rohingya looking face on a latrine

One of the few signs utilizing all dominant written languages used in the camp:

Burmese (1st row) Bangla (2nd row) English (3rd row)

The reality for the inhabitants of the camp in Cox’s Bazar is one of confinement. Most Rohingya have no rights to employment or education in Bangladesh; their only opportunities are what is furnished by the government or NGOs within the camp. Police checkpoints pepper the roads radiating out from the camp. Vehicles are often stopped and searched by police, not looking for Rohingya stowaways (as I first suspected) but black market goods from the camp—rice, lentils, and oil provided by the World Food Programme.

What were refugee families fuying with the few Bangladeshi taka they could scrape together from selling rice they had waited for hours on a scorching hot day to collect? Most frequently, medicine from local pharmacies and fresh food (meat, fish, vegetables, and eggs), suggest the findings from an OXFAM study released not long after I arrived. Even at a severe discount, the Rohingya were smart enough to know a person can’t subsist on rice and lentils alone.

For the Rohingya who pursue livelihood activities outside of the camp, a series of bribes are likely required; paying camp and forestry officials if they wanted to collect firewood in the forests, for example. In one household we interviewed, a woman was absent because she worked in a garment factory in the area; one of the lucky few who how found a way to secure employment outside of the camp. Meanwhile, some authorities acknowledge that the cheap labor force is good for their bottom dollar, so heads have turned while Rohingya have been used as cheap labor for construction, in salt fields, and at shipping ports.

And yet, it would be difficult to argue that the Rohingya aren’t industrious. When I first arrived in October 2017 the newest camp areas were a buzz of activity. Men and boys marching with heavy bundles of wood on their shoulders, harvested from the nearby forest. You couldn’t walk through these areas without risking your head, as long pieces of bamboo were carried at shoulder height along dirt paths. Everyone was scrambling to use available resources to build shelters, stock up on fuel for cooking, and maybe sell a little surplus to supplement their rations. I quickly realized some were incredible artisans, watching them deftly weave mats for seating or shelter walls, shaping cement into an earthen stove, or laying a perfectly symmetrical cement slab beneath a water spigot.

When I returned in May 2018 I found the markets within the camp looked more numerous and more plentiful—a triumph of entrepreneurial efforts and sheer necessity. Rohingya tailors hunched over manual sewing machines were fighting to regain their art form and livelihood. A few surprisingly fat cattle sauntered through the middle of the camp. Space is a limiting factor for most agricultural activities, but where there is a will a way emerges.

Some of the older refugees have managed to hold onto tiny kitchen gardens attached to their shelters. It wasn’t surprising to realize, mid-interview, that you were sitting next to a prized hen sitting on a clutch of eggs in the family’s living space. One household we visited had converted the front half of the structure into a chicken coop, and we had to wade through the clucking pullets to conduct our interview; precious living space sacrificed to eke out a modest living.

A hen sitting on a clutch of eggs in a shelter

Keeping the peace between an original population and a newly displaced population has its challenges. In a humanitarian crisis, there is the tendency for NGOs to provide aid to the displaced population but overlook the original host community—whose resources may also be severely strained during the crisis. In Cox’s Bazar, locals have expressed discontent over the increase in the price of basic goods and diversion of aid towards Rohingya.

As lovely and kind as I have found the Bangladeshi people to be, the tactics of “othering” have been effective in some cases. Comments about the refugees morality (“they steal”) their reproductive irresponsibility (“they breed like rabbits”) their economic burden (“they steal our jobs”)–all these trickle past the lips of the those outside the camp to justify this containment—mirroring the same worn out rhetoric used by politicians and governments around the globe.

Resentment has at times boiled over into attacks against refugees in the camp by local gangs. In contrast, there exist many accounts of established Rohingya and local Bangladeshis providing food, shelter, and protection to newly arriving Rohingya. Simultaneously, cultural and religious characteristics have enabled meaningful interaction between Rohingya and local Bangladeshis, with a significant amount of intermarriage overtime.

In addition to the extreme trauma and other human rights violations experienced by many Rohingya in Myanmar, refugee camps are replete with daily stressors. Chronic lack of food and a poorly diversified diet is an ongoing physiological stressor. Coping strategies include reducing meal size, consuming fewer meals per day, and elderly family members giving their meals to younger children. We heard accounts early in the response of families who had split into two households in order to increase the rations they were allotted—a change that may have increased their rations at the expense of the protection of a larger family unit.

Restrictions on the ability of refugees to work or develop a livelihood to improve their family’s status render many bored and restless. Limited formal employment activities have pushed some Rohingya into organized crime—further straining the relationships between the Rohingya and the local Bangladeshi population. The culmination of all these factors means the Rohingya population is highly vulnerable to exploitation.

Smuggling and human trafficking networks have targeted the Rohingya, especially those attempting to leave the camp. Gender-based violence has increased, children are vulnerable to kidnapping and human trafficking, and there have been reports of women being approached by foreigners and recruited for “jobs” outside of the camp, only to disappear. Births of new children are undocumented by the authorities, increasing the risk that trafficked Rohingya children are untraceable. Reports of survival sex, marrying daughters off earlier than normal, and men taking a second wife for economic or protection purposes are also coping mechanisms. Prostitution by women and girls is, in extreme cases, the only way they can provide for their families without employment opportunities in the camp.

A young child being assessed for malnutrition

Despite the immense challenges of life in the camp, childhood still peeks through the cracks. Wandering past a bamboo structure acting as a school one day, I overheard small shrill voices repeating their teacher in unison “Hello how are you?” “Hello, how are you?!”, “What is your name?”, “What is your name!?” I peeked inside and saw big bright eyes enthralled by the lesson. This kindergarten class’s gusto for learning was not yet extinguished by the lack of future opportunities.

Kites are constructed from discarded plastic, swings made from rope and rice sacks hang in the narrow walkways between shelters, rudimentary cars with plastic bottle cap wheels are pulled along by a string through the dusty roads. One day we caught a gaggle of kids sliding down a dusty embankment on rice sacks, which made me think of winter sledding as a child. The moment when a young boy started making armpit farts to impress his friends I could only laugh and shake my head. At the end of the day, a child in a Refugee camp in Bangladesh is no different than a kid in any other country—the only difference is circumstance.

Two Rohingya girls curious about our antics

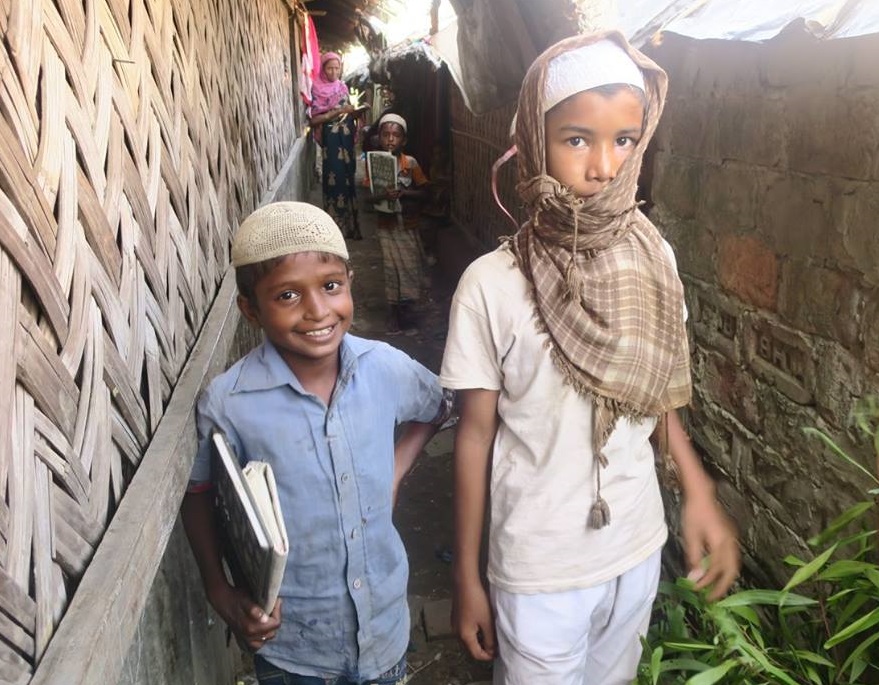

Two Rohingya boys returning from school

As dearly as I fight to maintain my optimism, I’m afraid I do not have a happy conclusion for this article. The plight of the Rohingya is dire—which is why the United Nations has referred to them as the most persecuted minority in the world. Their existence in the refugee camp of Cox’s Bazar is a life in limbo. Although the Government of Bangladesh has poured resources into supporting the refugees, their hospitality has a limit. When I first arrived in October 2017, the Rohingya were being referred to as “Displaced Myanmar Nationals”. Upon my return in May of 2018, the term had shifted to “Undocumented Myanmar Nationals”, a term that alludes to illegality. A recent push by the Government of Bangladesh to relocate Rohingya to a sinking island in the Bay of Bengal is alarming.

One of the Rohingya I met, a man named Hassan, served as our guide in the camp. His quick to smile nature and joyful character made me wonder how he had managed to maintain his optimism in this difficult environment. His level of English was impressive, something he’d dedicated himself to learning in an English class provided by an NGO. The last day before we left Hassan showed us his home in the camp, beaming with pride as he pointed out the simple structure and small kitchen garden, displays of his efforts on the canvas he had to work with. His Facebook biography reads “I’m a registered Rohingya refugee […] currently living in Bangladesh for about 26 years”. Given the history of this place, I imagine Hassan will be in the camp at least another twenty-six.

In a candid conversation with one Rohingya father, he confided in me “we want to stay here. We want to work towards Bangladeshi citizenship and become good Bangladeshis”. His sincerity was heart-wrenching. Would the Government of Bangladesh ever give them that chance? The likelihood that Bangladesh would embrace the Rohingya is slim. Over tea with one of my more progressive Bangladeshi friends in Dhaka, the nation’s capital, we discussed the Rohingya crisis. At one point my friend confided, a bit exasperated, “I wish our government could just give them legal status. We are already an overpopulated country, what is one million more?” I nodded my head in agreement as I sipped my tea.

As pragmatic as this may sound, it’s an unlikely outcome, and in direct opposition to the actions taken by the Government of Bangladesh since the earliest Rohingya movements across the border. Which is understandable, as Bangladesh is a lower middle-income country with one of the highest population densities in the world. How could I wish for Bangladesh to welcome the Rohingya into the tapestry of their country, when far richer and less crammed nations were turning away boatloads of desperate refugees? The more likely outcome is a series of tense resettlement agreements signed between Bangladesh and Myanmar overseen by the UN, which neither secure their safety nor improve the stateless condition of the Rohingya.

The love of a father for his child

In short, the plight of the Rohingya is a stain on our collective humanity. Their persecuted status is a tale sparked by colonial-era divisions, set aflame by state-sanctioned violence, and kept smoldering through politics of othering. The Rohingya are people without a place, considered Bangladeshi by Myanmar and Myanmarese by Bangladesh. They fled from Rakhine state—what has been described as one large detention center, to the largest refugee camp in the world in Cox’s Bazar. Their choice lies between two environments of extreme restriction, with Myanmar the more violently lethal option. The chronic statelessness of the Rohingya is long overdue for an enduring, international solution. The lingering question is, what?

Note: Names have been changed to protect anonymity.

Definitions

burqa: a garment worn by women in some cultures and traditions to show piety and modesty; composed of a long flowing garment which covers the entire face.

hijab: a garment worn by women in some cultures and traditions to show piety and modesty; composed of a long flowing garment which covers the head and neck while exposing the face.

lungee: a striking, skirtlike garment often of brightly colored silk or cotton worn in South Asia and Myanmar.

niqab: a garment worn by women in some cultures and traditions to show piety and modesty; composed of a long flowing garment which covers the entire face except for the eyes.

paan: a mild stimulant consumed throughout South Asia prepared by wrapping areca nut in betel leaf

purdah: the practice in certain Muslim and Hindu societies of screening women from men or strangers.

taka: the national currency of Bangladesh.

tupi: term used on the Indian subcontinent for a short, rounded prayer cap.